A Quick Anatomy Lesson For Ewe

- Sara Colburn

- Nov 17, 2023

- 3 min read

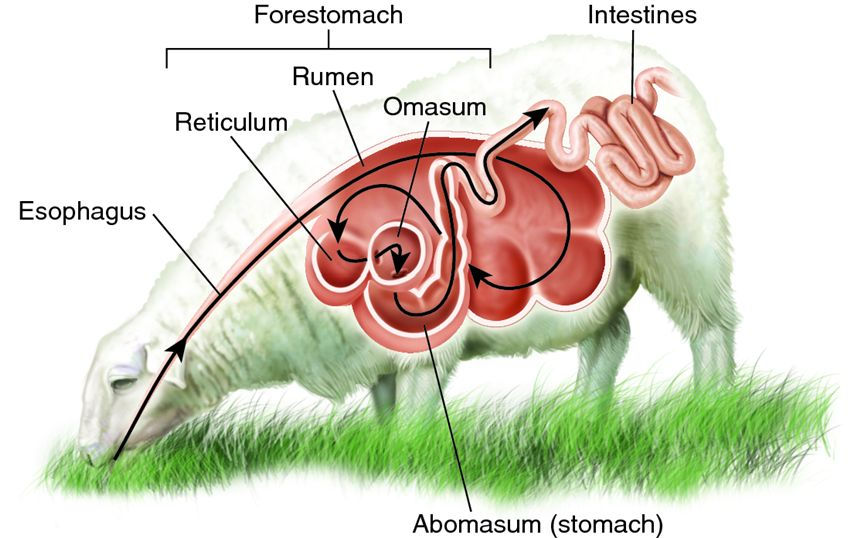

Today, let's dive into the intricate world of small ruminant digestive anatomy and some practical aspects of their care. First and foremost, let's set the record straight – sheep and goats don't have four stomachs, but rather a single stomach with four compartments – the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum.

First, food hits the rumen, a vast fermentation chamber where microbial magic happens. Microbes break down tough plant fibers, starting the digestion process. Once the initial meal is consumed, sheep regurgitate a portion of it, forming a cud. This cud is then re-chewed, aiding in further mechanical breakdown and mixing with saliva, which contains essential enzymes for digestion. The re-chewed and moistened cud is then sent back to the rumen for continued microbial fermentation, extracting maximum nutrition from the forage. Next, in the reticulum, it separates the good stuff from the not-so-desirable bits, making sure only the finest gets sent to the next digestive chamber. The omasum is the compartment that squeezes out excess water, ensuring our sheep and goats stay hydrated, even in the driest of times. Last but not least, we have the abomasum – the true stomach. Here, acids and enzymes break down the remaining nutrients into a form the body can absorb.

Here in Ohio, where the grass takes a winter hiatus from November to March, it's essential to remove our fuzzy friends from pasture during this period. Instead, provide free access to high-quality hay forage and a balanced free-choice mineral supplement to ensure their nutritional needs are met. While you don't need the most expensive hay around, a mold and weed free mix is essential. Fed in feeders off the ground. (We can discuss setting up feeders to minimize expensive waste in another post 😉). I also struggled to find a good loose mineral aimed at sheep. Beware if you have mixed flocks because sheep CANNOT be fed goat mineral due to their copper sensitivity. I ended up finding what I needed at Rural King.

Now, let's tackle the unwelcome guests in the digestive tale – intestinal parasites. From strongyles, notably the notorious haemonchus (aka barber pole worm), to coccidia and tapeworms, these critters can disrupt the harmony in our flocks.

Since we've discussed how sheep digest their forage, we can discuss the importance that plays on parasite mangement. Highest in importance is pasture management, a vital aspect of ensuring the health and vitality of our flocks. Responsible pasture rotation is key; it's not just about what they eat, but also how they graze. Keeping the grass over 4 inches prevents overgrazing and reduces the risk of parasites, which tend to lurk closer to the ground. Monitoring moisture is also important as that is how the worms move through the field. They are not able to move on their own, they rely on water to carry them to new places.

Regular hands-on monitoring is the key – evaluating body condition scores, FAMACHA scores and conducting fecal analyses. These diagnostics are critical in determining an appropriate deworming protocol. All of these will be discussed in the coming posts!

And speaking of deworming, let's dispel a common misconception – it's not a one-size-fits-all affair. Deworming on a set schedule or treating every animal can lead to parasite resistance. Instead, it's about understanding your flock's unique needs. In this blog, we'll guide you through the process of conducting your own Fecal Egg Counts (FEC) and collaborating with your vet to develop a tailored care plan for your animals. That's what we'll be exploring in the coming weeks!

As a disclaimer, I am not a veterinarian or a nutritionist. I always defer to the professionals in cases of sick animals.

Comments